Now that it seems to be ending, what has this period of enforced online exhibiting taught us? A distribution system that we took for granted (exhibition is installed in gallery, audience looks at work of art, exhibition is deinstalled, audience remembers or forgets exhibition) was stripped away overnight. What was left (unless you were fired) was an industry of arts workers without a program. Since then, workers have been busy digitising everything, but have we clicked? If we have clicked, out of interest or duty, we have looked, but what have we seen? What, if anything, have we remembered?

Of this period I will remember the exhibitions mounted in “simulated” gallery spaces—The Potter Museum of Art just launched one. These digital galleries are like video game versions of existing or imagined rooms; The Potter has recreated its upstairs gallery rooms. Reproductions of art are then “installed” as images pasted flat on the walls of these facsimile rooms. Like an interior Google Map, you click around the room and scroll up to a “work”. I am moved by the labour that has gone into these digital “solutions” for the estranged public, but at the same time let us all admit: these things don’t work. With the upmost respect for the effort that it took to create these airless exhibitions, we must leave this model behind as a monument to our lockdown sins.

It turns out that making art for the internet is hard. It turns out that is a skill, if not outright an innate talent. I have a newfound appreciation for artists who create art for the internet—I don’t mean art about the internet (although I taught Hito Steyerl to undergraduates over Zoom recently. The appropriateness of looking at Steyerl exclusively online was immediately apparent to all, newly enriched by compulsory cyber-study, and we savoured the experience). I am talking about artists who create with and for the internet as an extension of their daily practice. Instagram is the place were visual artists dwell online. There are users who the Instagram algorithm sends me as a priority. These artists process their aesthetic-thought through Instagram. The users I like hardly post their artwork, but rather inspirations, jokes, political concerns, visual ideas, or small corners of their life. Their posts are not forced. No one’s making them do this. The algorithm services my enthusiasm for these (heavy air quotes) “content creators” and their posts come up first. “You’ll like this”, the algorithm says (and I do).

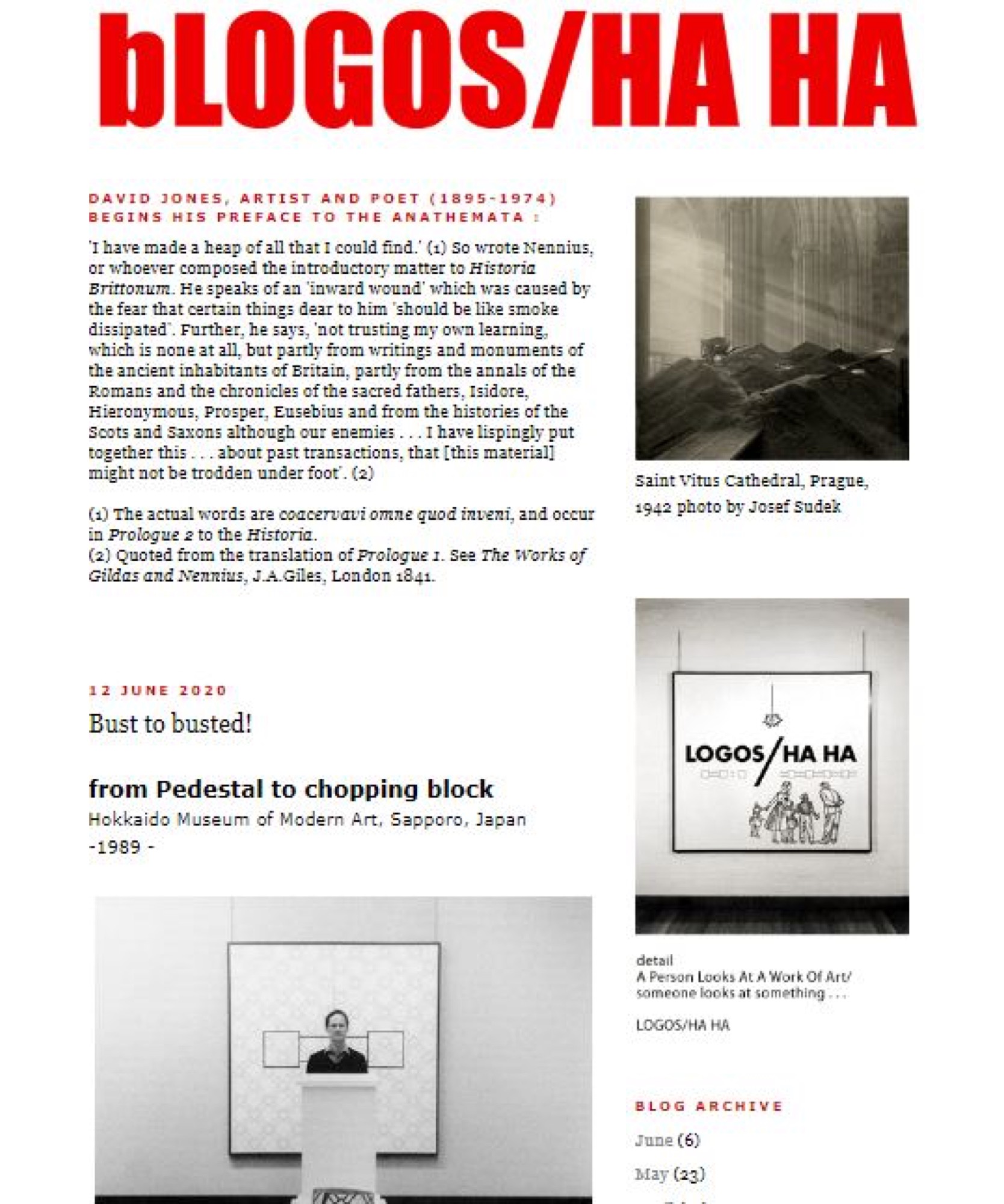

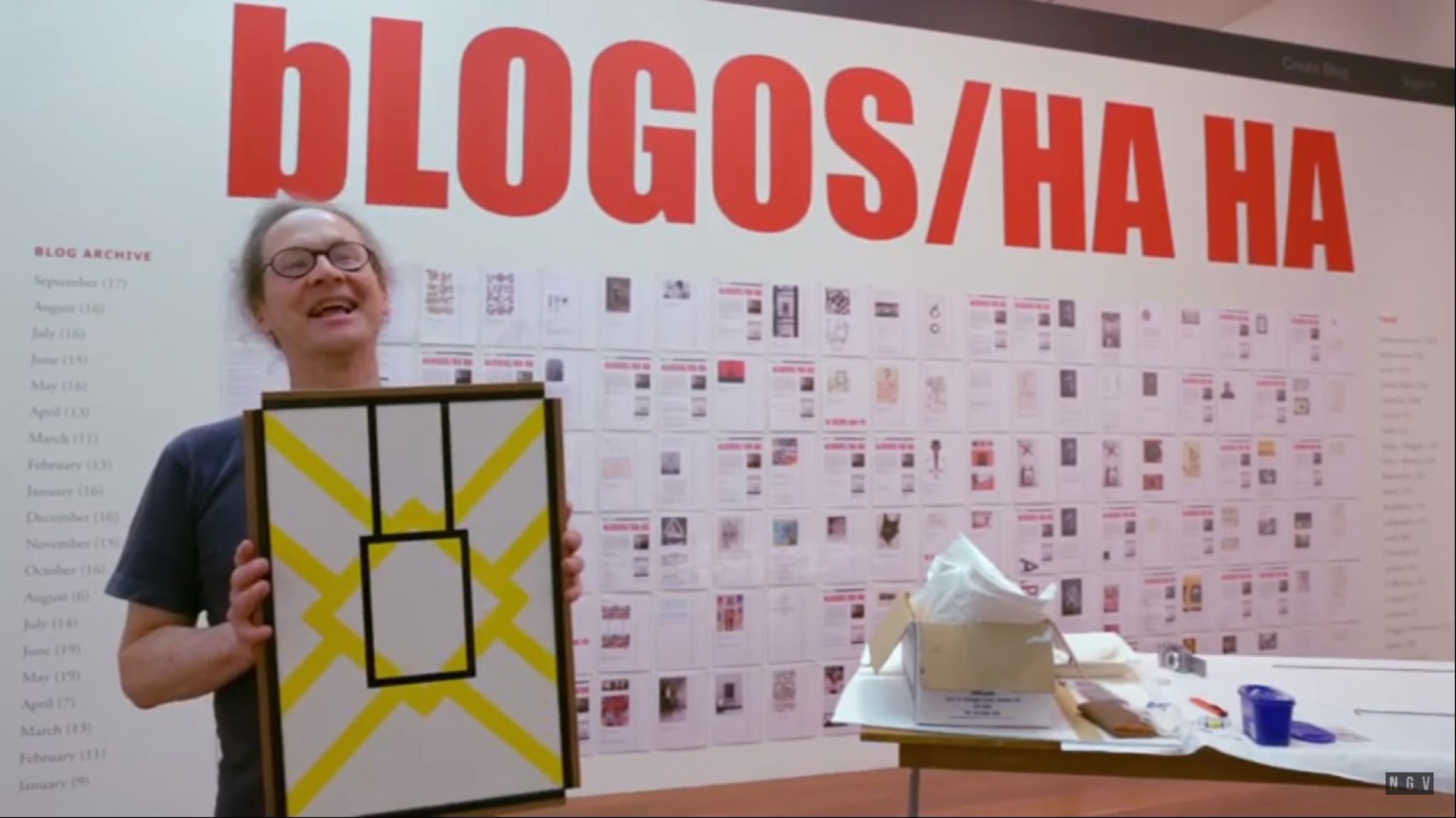

Peter Tyndall’s long-running blog bLogos/HA HA is an exhibition space that I have returned to frequently during this period. The Instagram users I refer to above are exclusively young artists, but Tyndall (who is represented by Anna Schwarz Gallery) is firmly established. Tyndall, however, at 69 years of age, is bloody good at the internet. Better, I’d argue, than most millennials. He started bLogos/HA HA in 2008, and it has been a digital arm of his daily practice ever since.

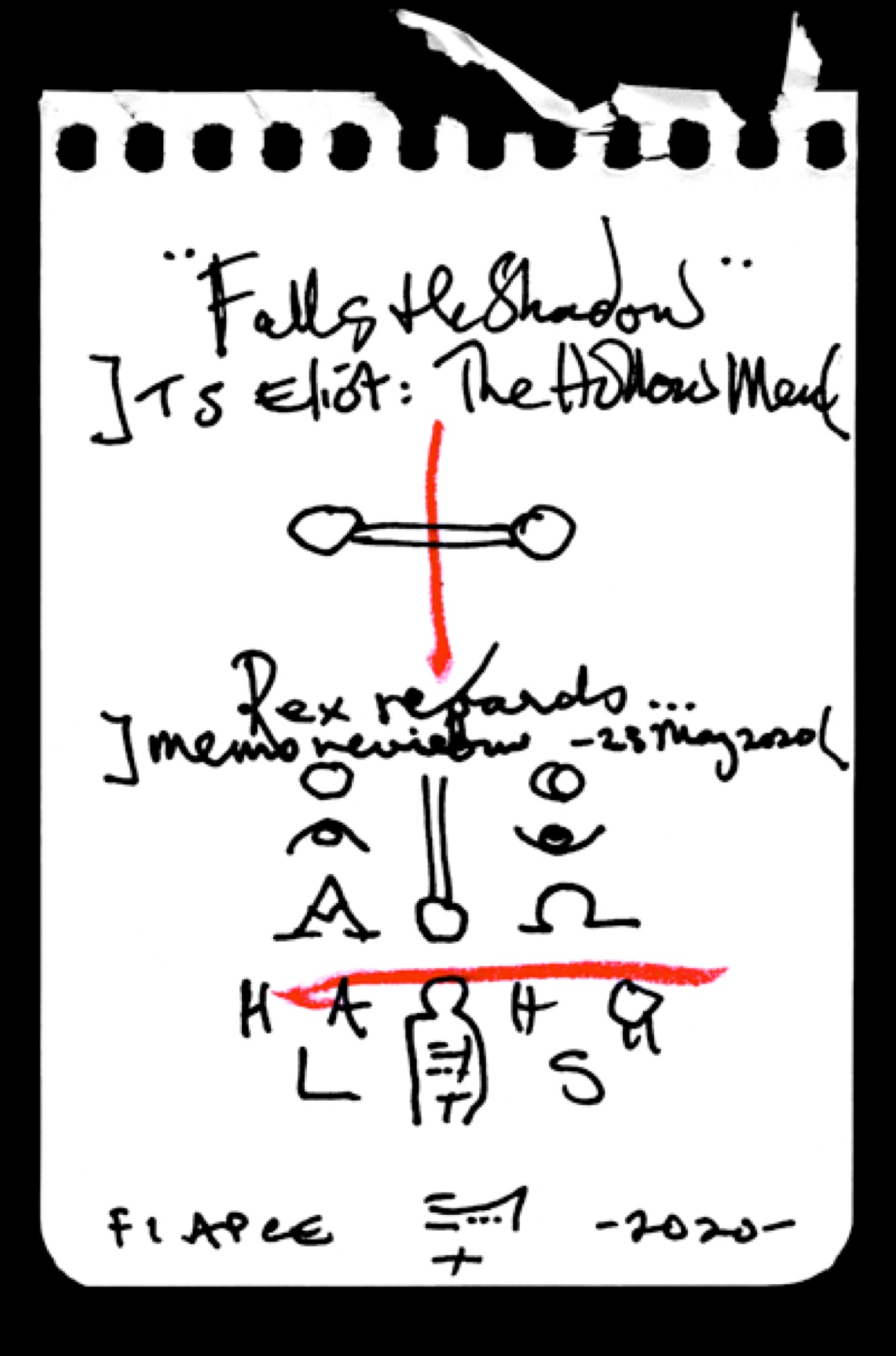

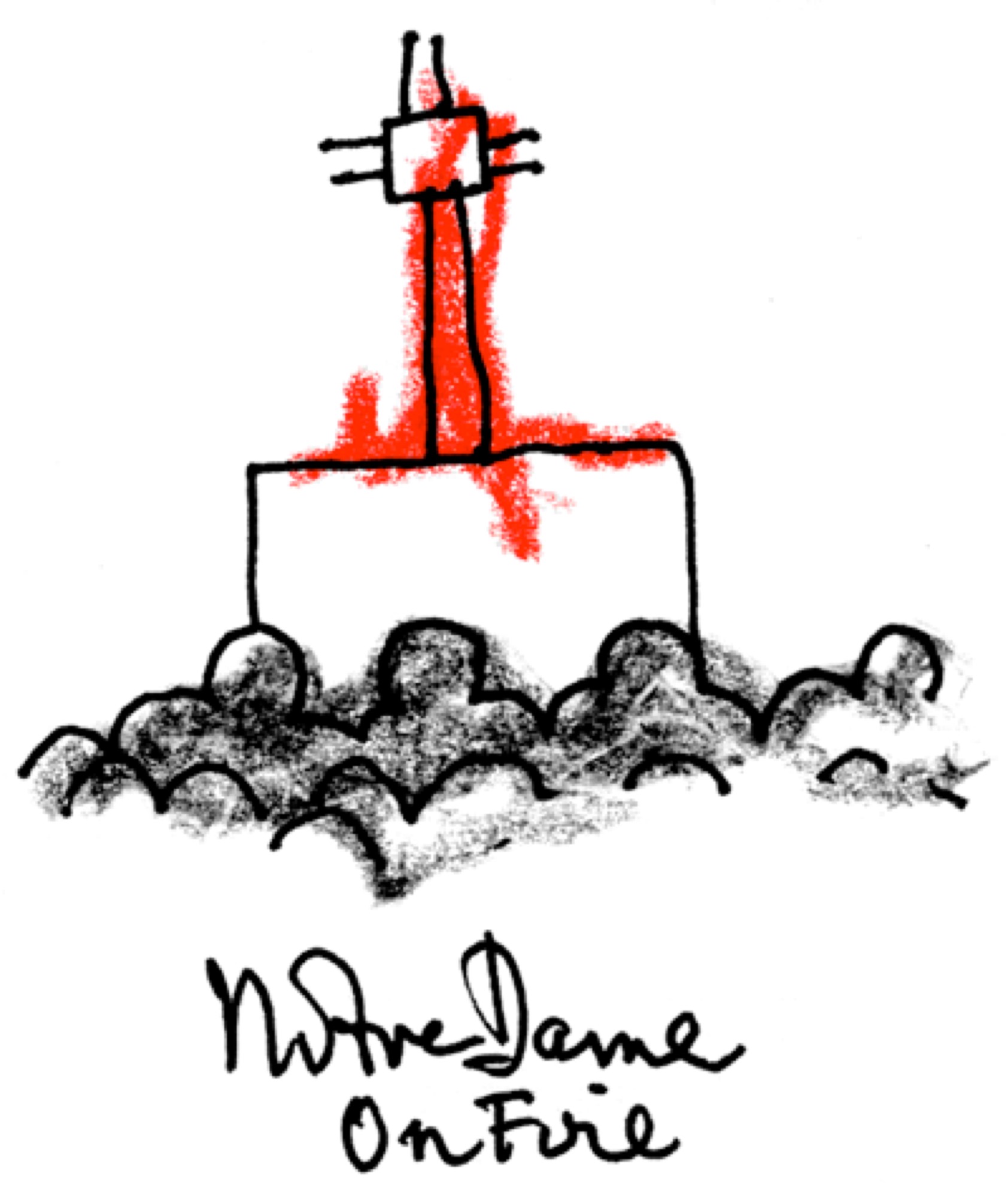

Tyndall’s blog has a reportage structure. He sees things of interest and copy-pastes the information (images, text, links) directly into his post. This digital collage-style—a vacuuming up of press-releases, auction notices, online reviews—leans heavily on the concept of connoisseurship. Tyndall is archiving his interest in art, and his posts express this obsession with seeing aesthetically. More than record-keeping, Tyndall will always comment some way on his found material. These additions are often cryptic and come in no standardised form: it might be selective quoting, or highlighting text that Tyndall finds particularly significant, but it is most commonly a caption on a found image that reads “Theatre of the Actors of Regard” (indicating that his co-opting institution (abbreviated to TAR) has taken possession of that image), or a short reflection, written in second-person perspective, from “your correspondent”. Sometimes Tyndall will create a responsive artwork, usually a drawing, related to the material in the post. If we are lucky, he will occasionally turn these images into GIFs, like his memorable, ridiculous one of legendary author Gerald Murnane (see above).

If you go to the blog today, you will first find his landing-quote, which is on every page and which reads in part: “I have lispingly put together this … about past transactions, that (this material) might not be trodden under foot”. In his recent posts are reflections on the destruction of statues depicting racist, colonialist and “monstrous” historical figures, a link to an excellent online video material on artist Helen Maudsley produced by The Potter, posts devoted to television shows that Tyndall has watched/is watching (it’s often not clear if the artist is posting because he has witnessed something that day or if he is free-associating), a meditation on the lateral brain and Rembrandt, a note on a past work of his about to be sold at auction, and an in-depth reflection on a Memo Review from a few weeks ago (posted after the idea for this review was already born, but the responsive speed of Tyndall’s posting outstrips our lumbering weekly post). His blog has kept up the stamina of over ten posts a month for twelve years now.

The content Tyndall creates on bLogos/HA HA, like his painting practice, is about looking at art. The title used for every piece he makes has been approximately the same for over four decades:

detail

A Person Looks At A Work Of Art/

someone looks at something …

LOGOS/HA HA

This title is also used to “sign-off” each blog post, indicating that each post is a “detail” of a single work that Tyndall is continuously making. Tyndall has changed this title over time. In 2014 Tyndall linked to a review written by artist/critic Robert Rooney, with a comment on this artwork title:

Since the late ‘70s, Tyndall has given all his works the (same) title … The meaning of these words should be clear to all, yet for some people this strategy seems to create a barrier between the work and the viewer. I am tempted to think of this as something akin to the “ha ha” in 18th century landscape gardening whose purpose was to ensure that the cattle kept their distance.

Tyndall had used the HA HA phrase in earlier artworks, but this description of the ha-ha, which is a sort of pit that creates a “barrier while preserving an uninterrupted view of the landscape beyond”, clearly resonated with the artist, and sometime after this review from 1987 Tyndall incorporated HA HA into his title.

Like Rooney wrote, we all understand “the meaning of these words” in Tyndall’s title, the sentences aren’t complex, but the consequences of this title are often difficult for viewers. Like cattle, we look at Tyndall’s work, invoking the action predicted in the title, but the act of looking is somehow arrested by the awareness that this looking is constituting the work. The “someone” in someone looks at something … is you. In this instant feedback loop, what is before us is suddenly bound to us.

While I like Tyndall’s gallery work, which you can see on the Anna Schwarz Gallery website, his brand of postmodern play, born deep in the wake of the conceptual art moment, never feels more vital than on bLogos/HA HA. From experience, the blog doesn’t make sense until you have grasped the punning framework that sustains it. It takes some repeat viewing. Yet in that viewing you will find Tyndall leading you through looking. One picture will immaculately beget another image, and in the association Tyndall offers you a thread to follow. Perhaps, if the logic is too sublimated, Tyndall will write a comment, or redraw the image in some way; he might photoshop the original image with his signature yellow rectangle lattice-design, which is both a structure to hang something on and a frame to see something through.

Tyndall’s omnivorous looking at art means that his blog is perhaps the most devoted interpretation of local art history I can think of. Although his interest in art is broad, his position as a key figure in Melbourne’s contemporary art scene in the 1970s and 1980s makes him articulate Australian art as an “insider” would. He has the same fondness and nostalgia for the generation of Melbourne artists preceding him that the Geelong-born artist Ian Burn had. Tyndall is perhaps an illustration of Burn’s prioritisation of the artist over the historian in his essay titled ‘Is Art History Any Use to Artists?’ (1985):

Pictures embody an historical understanding and practice which links them to particular artistic and cultural traditions, classes and societies. That understanding is built up largely through the way an artist notices and looks at art … History isn’t just a ‘background’, or a set of occasional references, but is infused in the creative process.

Rather than being arrested by the task in front of you as a viewer (blog-reader), Tyndall’s blog invites you into the creative process of reconstituting a history of the art-image. His second-person narration prioritises you as the “eyes” of the blog, seeing in these pictures what he (the artist) sees.

Blogging as an internet medium is almost antique. Nowadays there doesn’t seem to be anything daggier than a blogspot—although the early Web 2.0 vibe is retro enough to be exploited by some of Melbourne’s hip millennial scenes like whitecuberd, Meow and the now extinct Melbourne Fine Art Gossip Blog. Mainstream Internet culture has moved on to the “micro-blogging” format of character-restricted tweets, Instagram captions, or 15 second tiktok videoclips. I am instead reminded of Gerald Murnane’s archives of files, in which he has buried decades of fictional work. Tyndall, a Murnane fan, in posting his frequent missives, makes his work visible to others, whereas Murnane’s is locked away in a collection of ever-filling filing cabinets.

This connection back to physical archive keeping is telling, as the original action Tyndall’s blog most recalls is the neo-avant-garde practice of mail art networking that flourished in the 1970s. Mail art is a medium that Tyndall still participates in. A search on this blog for post reveals that the Tyndall family once owned a “pharmacy and gift palace” next to the Kangaroo Flat Post Office, and that Tyndall was once sent “3000 items” in one year by his friend the artist Robert MacPherson. Impatient for true global networks, the world’s artists took to weaving a web of correspondence that formed an internet practice before the internet existed. MacPherson lives in Toowong, a suburb of Brisbane, and Tyndall in Hepburn Springs (two hours from Melbourne); as two “regional” artists, they demonstrate that the distance and isolation of the periphery has historically bred intensely communicative art.

While Tyndall’s project needs to be considered in relation to the history of mail, and perhaps even more obviously the history of archive art, before this can happen it needs to be accepted as an artwork itself. This was done in the brilliantly chaotic Melbourne Now exhibition at the NGV in 2014, in which bLogos/HA HA was represented by a touchscreen interface, but also as a kind of mural pasted up on the gallery wall. Here we have the reverse of our current problem: instead of offline artworks being awkwardly placed into digital rooms, the Melbourne Now display proved that exhibiting internet art IRL can be equally frustrating.

I am not sure how we can possibly document and remember the struggle of the Covid-19 lockdown, with all its interconnected real-world perils mediated through the communicative frame of the internet screen. I’m just an art historian. But I am sure that artists like Tyndall and those millennials on Instagram who I am so grateful for, will show me how. As Pamela Hansford wrote in her 1987 catalogue Peter Tyndall: dagger definitions,“Tyndall clearly loves looking, and loves the look of others looking”. Tyndall’s reminds us that once, before being online became such a chore, we loved looking at—gazing into—the internet.

Victoria Perin is a PhD student at the University of Melbourne.